Imagine your body’s immune system as a highly skilled security team, constantly patrolling to keep you safe from harmful intruders. Sometimes, in its efforts to defend you, it can create a unique structure called granuloma. Granulomas are small areas of inflammation that can form in various parts of the body, often in response to an infection, inflammation, or the presence of foreign substances. While they are a natural part of the immune response, granulomas can sometimes cause health complications if not properly understood and managed.

Granulomas are small nodules of inflammation that form as part of the body’s immune response. They are essentially clusters of immune cells that come together to wall off substances that the body perceives as foreign but is unable to eliminate. This defense mechanism is intended to isolate and contain foreign substances, preventing them from spreading and causing further damage.

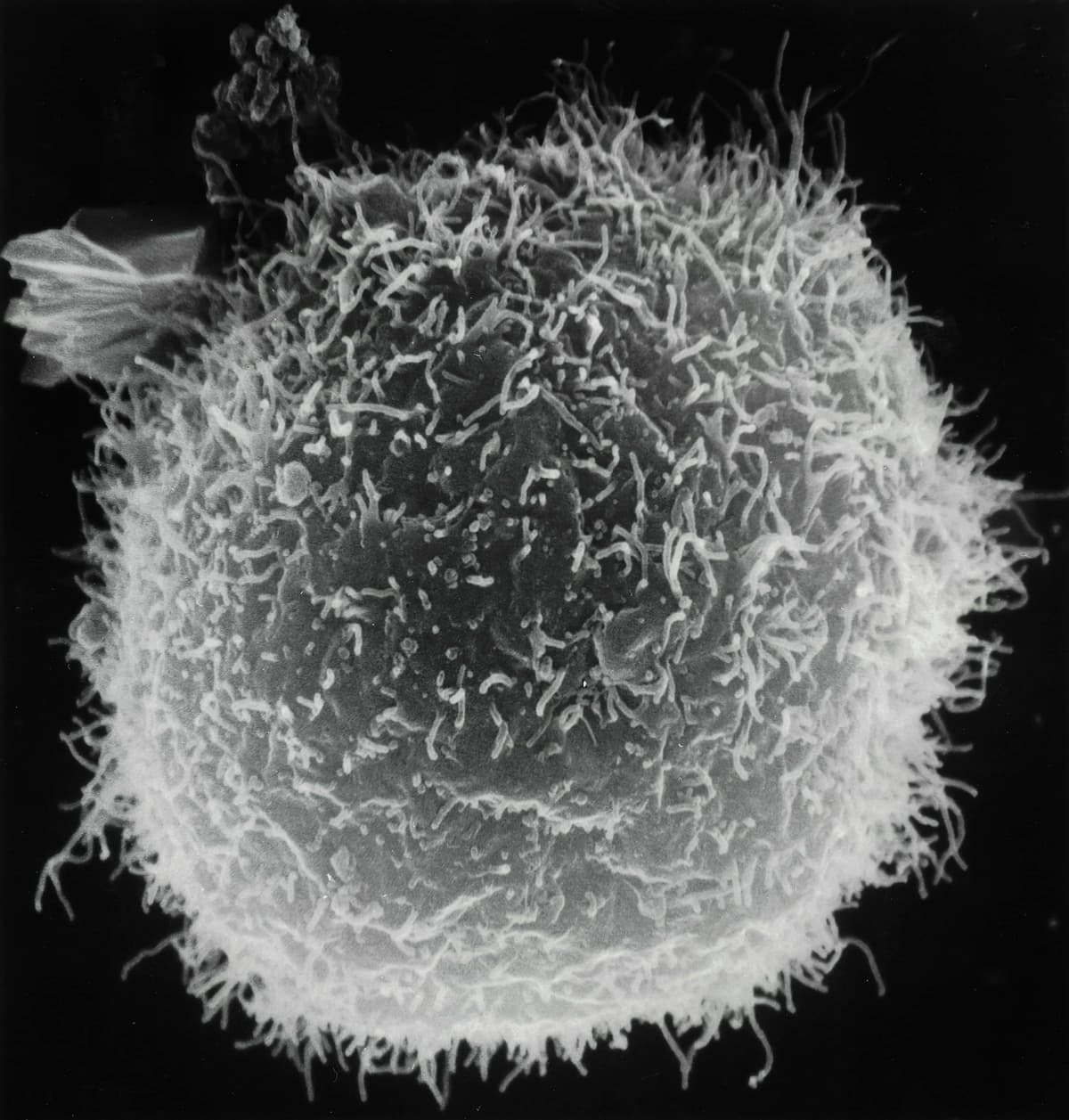

Medically, a granuloma is defined as a cluster of macrophages, a type of white blood cell, that transforms into a more specialized form known as an epithelioid cell. These cells are often accompanied by other immune cells such as lymphocytes and multinucleated giant cells, to form a structured, organized nodule. This organized immune response can be identified through microscopic examination of tissue samples.

The formation of the granuloma begins when the immune system detects a persistent irritant or pathogen. Unable to destroy or remove this invader, the immune cells cluster around it to form a barrier. This process involves the immune system recognizing the foreign substance, then recruiting immune cells to the site before transforming the macrophages into epithelioid cells to form a barrier, capturing the irritant and thus creating a granuloma.

Granulomas can be classified into two main categories: caseating and non-caseating.

Caseating granulomas are often caused by infections and feature a central area of necrosis that appears cheesy or crumbly. Tuberculosis is a classic example of this. The central necrosis results from the immune system’s attempt to contain the pathogens or foreign substances it can’t eliminate.

Non-caseating granulomas, which are typically caused by an inflammatory condition, lack the central necrosis and have a more uniform structure. Conditions like sarcoidosis, Crohn’s disease, and berylliosis usually produce non-caseating granulomas.

These categories can be broken down further into different types of granulomas, based on their etiology, histological features, and underlying pathophysiology. Each subdivision provides more precise information that helps in diagnosing the specific cause and determining the appropriate treatment.

Granulomas can form due to a variety of causes; each triggering the body’s immune response to isolate and contain substances it considers foreign or harmful. These causes can be broadly categorized into infection, inflammation, foreign substances, and autoimmune disorders.

A common cause of granuloma formation is infection. When the body encounters pathogens that are difficult to rid of, such as certain bacteria, fungi, or parasites, granulomas may form to prevent the spread of these organisms. For example, tuberculosis is a well-known infectious disease that leads to the formation of granulomas in the lungs. Similarly, fungal infections like histoplasmosis can cause granulomas in various organs, including but not limited to the lungs and skin. Parasitic infections, like schistosomiasis, can also lead to granuloma formation as the body attempts to isolate the parasite eggs.

Chronic inflammatory diseases often lead to the formation of granulomas. Sarcoidosis is an example of this, where granulomas develop in multiple organs, most commonly the lungs and lymph nodes. Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel disease, is another condition where granulomas can form, mainly affecting the gastrointestinal tract. In such cases, the body’s immune system reacts to persistent inflammation by creating granulomas to contain the inflammatory process.

Granulomas can also form in response to foreign substances that enter the body and cannot be easily broken down or removed. These foreign body granulomas typically develop around the material such as splinters, surgical stitches, spider bites, etc. Inhalation of certain particles like silica or asbestos could also lead to granulomas forming in the lungs. This type of granuloma is a defensive response, as the immune system tries to isolate and contain these particles to prevent further damage.

In cases where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues, this leads to chronic inflammation and granuloma formation. For example, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly called Wegener’s) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by blood vessel inflammation and granuloma formation primarily in the respiratory tract and kidneys.

The symptoms of granulomas can vary depending on the location and the underlying cause. In some cases, granulomas can be asymptomatic and are only discovered by medical imaging or examinations. In other cases, there can be significant symptoms and health issues.

Granulomas themselves are not typically painful or noticeable, but the inflammatory process and the effect on surrounding tissues can lead to symptoms. Common symptoms include fatigue, fever, and weight loss. These symptoms usually reflect the body’s immune response and inflammation rather than stemming from the granuloma itself.

Cutaneous granulomas, often associated with sarcoidosis or foreign bodies like stitches or splinters, can cause raised red or purple nodules on the skin. These lesions can be itchy or tender and could become infected if not properly managed.

In pulmonary granuloma, particularly tuberculosis and sarcoidosis, symptoms can include a persistent cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, and wheezing. In some cases, individuals could also cough up blood if the granulomas have caused significant lung tissue damage.

Granulomas that form in the liver or spleen, usually from infections or sarcoidosis, may not produce any specific symptoms initially. However, as they grow larger or more numerous, individuals may experience abdominal pain, an enlarged liver or spleen, and mild jaundice.

Ocular granulomas can cause symptoms such as blurred vision, eye swelling, itchiness, eye pain, redness, and sensitivity to light. These symptoms can be concerning, since they could indicate possible damage to vision if not promptly addressed.

Inflammatory diseases like Crohn’s disease could cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and weight loss. These symptoms can be severe and can significantly impact the quality of life.

It is also possible for granulomas to form in the brain or spinal cord, leading to neurological symptoms. These include headaches, seizures, changes in appetite, weakness, and impaired cognition, depending on the location and size of the granulomas.

Diagnosing granulomas involves medical history, physical examination, imaging studies, and lab tests. These tests can help providers identify the presence of granulomas, understand the possible cause, and provide appropriate treatment.

The diagnostic journey usually begins with a thorough medical history and physical examinations. Doctors ask about symptoms and their duration, any possible exposure to infectious agents or foreign substances, and known inflammatory conditions. Understanding the patient’s background provides context that can hint at the underlying causes of granulomas.

Imaging tests play an important role in detecting granulomas and assessing their extent and location. X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans are commonly used to identify characteristic nodular patterns that suggest the presence of granulomas. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can be used to provide detailed images to help pinpoint the exact location.

A biopsy is often needed to confirm the presence of granulomas and determine the cause. A small tissue sample is removed from the affected area and examined under a microscope. The appearance of the granulomas, especially the type of cells involved and their organization, helps pathologists differentiate between the different types of granulomas and their potential causes. However, since most granulomas are harmless, a doctor may not wish to do a biopsy right away.

Lab tests are done in coordination with radiology imaging and biopsy for additional clues on the underlying cause of granuloma. Blood tests can detect markers of inflammation and infection, such as high white blood cell counts, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, and so on. There are also specific tests such as the Mantoux test, which diagnoses tuberculosis.

Treatment for granuloma varies depending on the underlying cause, location, and severity of symptoms. The primary goal is to address the root cause and alleviate any associated symptoms to improve the patient’s overall health and quality of life.

For granulomas caused by infections, the treatment is focused on eradicating the infectious agent. In cases of bacterial infections such as TB, the patient will have to take antibiotics over a prolonged period of time. For granulomas caused by fungal infections, treatment requires antifungal medication. Parasitic infections may be treated with antiparasitic drugs tailored to the specific parasite involved. When granulomas are associated with inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, anti-inflammatory medication is prescribed to reduce inflammation and shrink granulomas.

Surgical intervention is only necessary when granulomas cause significant tissue damage, obstruction, or other complications that cannot be managed with medication alone. For instance, if someone has airway obstruction, severe pain, or organ dysfunction, then surgery may be required.

Lifestyle changes can also play a role in managing granulomas. Patients are advised to maintain a healthy diet, exercise regularly, and avoid exposure to known triggers. Supportive care, including pain management, can help ease symptoms and improve the patient’s quality of life during treatment.

Granulomas are a natural part of the body’s immune response, forming in response to infections, foreign substances, or chronic inflammation. They commonly appear as skin bumps or lung nodules and are often resolved without needing treatment.

However, those with conditions like sarcoidosis or autoimmune disorders may experience recurrent granulomas that require attention. If you have these conditions or experience persistent symptoms, it’s important to discuss your concerns with your healthcare provider. They can explore various options tailored to your needs, to manage your condition and support your overall well-being.